Though it was published almost 40 years ago and describes a fictional civil war in South Africa, J.M. Coetzee’s short masterpiece Life and Times of Michael K might have been written about the ragged and riven USA in 2021. It’s not escapist reading, but then we go to high literature less to escape reality than to map it, and to voice our own objections, convictions, and ecstasies vicariously with the aid of a master geographer of the soul. Coetzee (pronounced cut-SEE-uh) is one of those. In this novel, he writes with Tolstoyan realism on the problem of helplessness, and on the brutality and depersonalization that arise as wrong answers to the problem of helplessness.

The titular hero, Michael K, is a gentle, quiet young man disfigured by a cleft palate, who works alone as a gardener in Cape Town. He has no family besides his ailing mother, for whom he cares doggedly and patiently, much as he does for his seedlings in the public garden. As the civil war grinds down the social order and institutions imagine solutions in the form of control, not help, Michael K becomes a refugee lacking basic human necessities like shelter, food, love, and freedom. Mostly, no one helps him. Under trying circumstances, people often retreat into guarded self-interest. But even those few who try to help Michael fail because they don’t understand what he wants, which is to help others, which is to tend the garden of life. He does that by exercising precisely the faculty that others lack in this novel: empathy.

“If you need help I can help,” Michael tells the old driver of a refuse cart who gives him a ride. “But,” Coetzee narrates, “the old man did not need help, nor was he in the mood for talk. He dropped K a mile past the top of the pass and turned off down a dirt track.” (p. 35) And Michael K finds himself alone again in the dry unsparing dust of the road, a dust reminiscent of that which John Steinbeck depicted swirling around the Okies on their way to California in The Grapes of Wrath. It’s as though planet Earth were a desert lacking not in water or food, nor even in compassion, but in mercy, in the willingness or wherewithal to actually provide emotional relief to those who need it through the exercise of empathy.

In the beginning of the book, Michael K fashions a makeshift wheelbarrow, tucks his mother into bed in it, and sets out for her hometown in the country’s interior so she can die there, according to her wish. It’s not a practical goal, nor even one his mother has asked to pursue, but according to Michael’s empathic logic, it’s the only thing that matters. As they pass through Stellenbosch, a picturesque town in the hilly Cape Winelands now overrun with military convoys, his mother’s heart failure worsens. Michael K turns for help to the Stellenbosch hospital, which provides palliative care but no solutions. After his mother dies, Michael K continues to haunt the hospital like a sort of ghost, a non-person. “Though he had no more business there, he found it hard to tear himself from the hospital,” Coetzee writes. (p. 33) The hospital too is a ghost of sorts. It looks like something human but is not. It’s a mirage of a mother, meant to care but unable to.

The one face of society that acknowledges Michael K’s existence is law enforcement. Obsessed with security, borders, and permits, the officers he encounters do not even try to help. On the contrary, they enforce the same impersonal law of neglect that seems to govern the inanimate universe.

“[W]ho is to say that twenty in four hundred is an unacceptable rate?” asks Major Noël van Rensburg, commandant of the Kenilworth resettlement camp, as he ponders the problem of death among prisoners. “People die, people are dying all the time, it’s human nature, you can’t stop them.” (p. 159) It sounds like something a Republican governor might have said over the summer. The Economist in July of 2020 compared the U.S. response to COVID-19 to “a hospital that invests in palliative care while abolishing the oncology department.” It was a summer of helplessness, anxiety, and brutality in which thousands died from COVID and federal shock troops fired tear-gas canisters at the heads of peaceful, unarmed protesters and at the medics who sought to provide them care. A mind like van Rensburg’s or Donald Trump’s cannot empathize, let alone help others. It can only imagine solutions in the form of control.

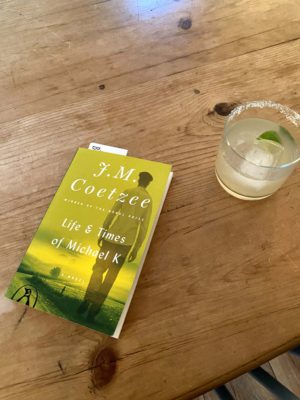

Helpless as Michael K is, he would rather die than succumb to control. No prison, work camp, or hospital can contain him, even when he’s starving to death and so weak that he can barely stand. Not even his own body’s demands for food can conquer his will. He is true to himself always, a character of a composite softness and toughness that is unique in literary memory. He is a gardener, a nurturer, a grower, a helper—a lover—in a brutal, neglectful world that neither loves him nor accepts his humble gifts. He keeps on giving them anyway. Armed only with a “persistent No” (p. 164) equal to Bartleby the Scrivener’s, and a packet full of pumpkin seeds, K silently endures. In a world where all are either jailers or jailed, he finds freedom by refusing to play the game. Perhaps it’s sometimes enough to endure until the season of death and violence passes and a new one begins, one that’s more fertile ground for mercy, help, empathy, and fairness. While we’re waiting, I prescribe Coetzee and a drink. The yellow-green cover of the Penguin edition of this book all but whispers, “Margarita and lime.”