A certain movie star will soon finish his run as Hamlet at Broadway’s Broadhurst Theater. Polonius and Laertes will again be safe from nightly perforation at the end of this actor’s sword, and Shakespeare’s play will also be safely out of his reach. It isn’t the first time that an accomplished movie star has entered the sublime domain of Shakespeare’s greatest play and engendered chaos. When Kevin Kline directed and starred in Hamlet for TV in 1990, he desecrated it in pretty much the exact same way.

In the famous “Alas poor Yorick” scene, Hamlet gazes at the old court jester’s skull and has this to say: “Not one now to mock your own grinning—quite chop-fallen!” Hamlet means that Yorick looks gloomier than he used to, i.e. “down in the mouth”—which is funny in and of itself since Yorick is not depressed, but in fact a corpse. And by “chop-fallen,” Hamlet also means that Yorick’s jaw has literally fallen off. Lines like this, entwining despair and humor, have made Hamlet famous for his depth and complexity. Hamlet uses cleverness, satire, and gallows humor to attack with words what he can’t attack with action: death, shame, powerlessness, self-hate. Hamlet’s defeatedness and softness mixed with murderous rage and dominance through wit are what defines him, and in this scene Shakespeare brings out his character in a very moving way.The gravedigger’s recollections imply that Hamlet was seven years old when Yorick died. Hamlet’s memories of riding on Yorick’s back and of Yorick entertaining him constitute almost the sole example of familial warmth in Shakespeare’s treatment of life at Elsinore. Hamlet obsesses over his father more than he expresses love for him, and the ghost of King Hamlet too does not love, obsessed as he is with his own misfortunes. The Yorick scene, however, like the hints of past love between Hamlet and Ophelia, demonstrates with great pathos what has been lost—not only a loved one, but mirth and love itself, which happens when “a noble mind is here o’erthrown” by grief, depression, rage, and self-hate.

What Kevin Kline did to these subtle lines recalls what Achilles did to the fallen Hector, which was to tie Hector’s corpse to the back of his chariot and, with a vain and ruthless ignorance of the meaning of life, to drag him behind his chariot around the walls of Troy. “Quite! Chop! Fallen!” Kline bellowed in a stentorian, public voice. He didn’t seem in the least curious about what the lines might mean, to say nothing of actually trying to act out the difficult mixture of humor and sorrow written there. He beat the phrase like a bass drum, ignoring the lovely falling meter of “chop-fallen,” a dactyl that conveys the fallenness of Yorick and of Hamlet’s heart.

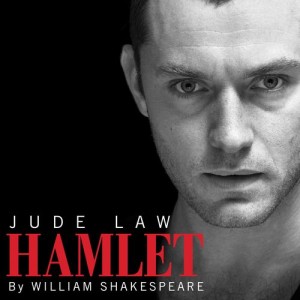

Kevin Kline was not there to read Hamlet to anyone. Was he there, maybe, to read his own name over the marquee? From Jude Law’s comments to the press, it’s evident that he savors this role for its prestige. He stated no qualms about taking on the huge challenge of understanding and revealing this difficult character. At the glorious moment of taking the stage as Hamlet, Law and Kline seem instead distended with pride and self-congratulatory joy. And why not, as long as they can also give the part what it deserves. The problem is that the role demands an intimate knowledge of self-hate, not self-infatuation.

Jude Law is less pompous in the role than Kevin Kline, but he’s equally brutal and unfeeling to the play. “My father’s brother, but no more like my father / Than I to Hercules,” Hamlet says in Act I. Everyone knows this is one of a thousand examples where Hamlet belittles himself in comparison to his father, where he asks himself “Am I a coward?” as he puts it directly in Act II. Hamlet wants to say, Claudius isn’t as good as the heroic and Herculean King Hamlet, and neither am I. The way Jude Law reads it, however, with great self-assurance, Hamlet might as well have said, “no more like my father than I to a refrigerator.” Jude Law’s Hamlet is interested in revenge and in Ophelia and in a good joke, but he’s not even slightly curious about himself.

In discussing one of the trademarks of Shakespeare’s characters, Harold Bloom cites Hegel’s notion of “self-overhearing.” This is Shakespeare’s device for dramatizing introspection and looking inside his characters. Hamlet is the most self-observant, self-overhearing character of them all, and without this trait the play loses not only its meaning but its plot and the coherence of its other characters. Without self-doubt, Hamlet cannot be the underdog and the hero we care about, and Polonius cannot by contrast be the supremely comic figure he should be.

According to the critic Vladimir Kataev, Hegel defined a comic character as one with an “invincible faith in oneself.” (Apparently, Hegel actually was comprehensible at least twice.) Polonius is all about that invincible faith in himself. He’s actually much farther from Hamlet’s nature than Claudius, who hates himself just like Hamlet and who envied the king, just like Hamlet. But Law plays Hamlet, not Polonius, as an invincible and hence ridiculous character.

You can practically hear the delicate apparatus of this great work of art seizing under the influence of Law’s performance which, to be fair, has a certain breathtakingly illiterate barbarism to it, like when the Taliban destroyed those ancient Hindu statues. And yet the audience gave Jude Law’s Hamlet a standing ovation. One of Chekhov’s characters, Mikhail Fyodorovich, tells a story of a man who applauded a play he wasn’t listening to (the man, who was drunk, said, “What’s he saying, something noble?”). I can only think that the audience, like Jude Law, came to the theater, as Fyodorovich says, “not for art but for nobility.”