“Hamlet is the finest of all the plays in the English revenge tradition,” says Roma Gill, editor of the Oxford School Shakespeare edition of Hamlet. Some would call that an understatement, since Hamlet is frequently invoked as the greatest play in any tradition. (Flaubert said, “The three finest things God ever made are the sea, Hamlet, and Mozart’s Don Giovanni.”) Hamlet is, however, a revenge play, a fact which often seems to go unappreciated by directors and actors and existentialist critics. Laurence Olivier was chilling in Marathon Man, but there was little of the revenge motif in his very stylized and emotionally beige Hamlet, who seemed to suffer from “indecision” as if indecision were akin to shingles, or something you’d find in the DSM IV, as opposed to a manifestation of inner conflict.

Who wants to watch Hamlet bitching about his terminal shingles?

Hamlet is about a war of the generations, between young and old, fathers and mothers versus sons and daughters. Claudius makes war on (and kills) his older brother, King Hamlet; Hamlet makes war on his uncle and his mother and their royal advisor Polonius; Laertes and Ophelia laugh at their father Polonius for being out of touch and giving stale old advice. Claudius, Gertrude, and Polonius make war on Hamlet; Polonius doesn’t trust his son Laertes and sends Reynaldo to check up on him; and of course King Hamlet’s ghost wants his younger brother dead and torments his son Hamlet with charges of filial debt and obligation, a sense of belittlement, and with his taunting, withdrawing, loveless apparitions and his absence.

At the same time, Hamlet honors and wishes to avenge his dead father, and Laertes feels the same way after the murder of his father Polonius, who he formerly laughed at. The ambivalent, “two-way” relations between the generations reflect inner conflict, a war of rage and guilt, and these opposing emotional vectors create a doubleness in the major characters. Hamlet resembles Laertes in mourning his father (and notes as much in Act V scene ii when he says, “For by the image of my cause, I see / The portraiture of his”); at the same time, in killing Laertes’s father, Hamlet has followed after Claudius, another father-killer. Claudius has boldly stolen his brother’s crown and his wife, but he suffers self-doubt, berates his own actions as “rank,” much as Hamlet frequently berates himself. Hamlet devastates his opponents with self-confident repartee and at the same time he remains meek and loyal servant to his father. The name Shakespeare gave to the son of Polonius, “Laertes,” seems to signify this instability of identity where sons identify with both their fathers and themselves; in Greek mythology, Laertes was not a son, but a father, the father of Odysseus, no less. Shakespeare has seemingly assigned the name to the wrong party, but it’s fitting, since rage and guilt are dynamic poles that split the characters’ personalities in Hamlet, warping identity, perception, and fate.

There is nothing native to Hamlet of the chemically inert, romantic substance fed into him by some of his interpreters on stage. As written, he’s a yin-yang of hate and self-hate, more hate and more self-hate. The role calls for an actor who can access guilt and rage during a performance, and it got just that in Zeffirelli’s movie version, because he had Mel Gibson, who portrays it flagrantly, on screen and off.

Harold Bloom says in The Western Canon, p. 365, “[T]he masterpiece of ambivalence is the Hamlet/Oedipus complex.” (The “Macbeth complex” is, according to Bloom, “the masterpiece of anxiety.”) Hamlet touches the same iconic themes as Oedipus Rex but has been realized with an unparalleled level of psychological realism. That’s why it’s not only the finest revenge play, but so much more.

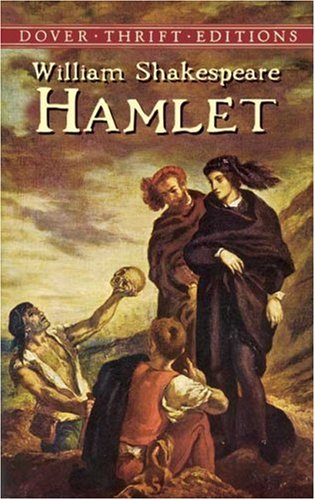

I like the Oxford School editions of Shakespeare; they’re meant for high school and college students and are straightforward, not self-serious, and their notes on the text are aligned vertically at the edge of the extra-wide page, so that you don’t have to hunt at the bottom for an explanation. Its cover photo, however, is of a Kenneth Branaugh whose expression is noteworthy for not seething with either hate or self-hate or, better yet, both.