The speaker of Ovid’s “Contrite Lover” elegy in Amores reflects on a quarrel in which he struck his lover. Full of remorse, he asks this of his own hands: “What have I to do with you, servants of murder and crime?” (Amores I, 7, 27). As Hermann Fränkel puts it, the speaker “feels estranged from his own self of a moment before. His identity is broken up….” (Fränkel, Ovid: A poet Between Two Worlds, pp. 20-21) The great classical scholar considers Ovid’s representation of inner conflict a historic literary achievement:

[I]t was an unheard-of novelty for the ancients that a person should no longer feel securely identical with his own self…. There is no sign of a previous emergence of these possibilities; Ovid took them for granted and used them freely in his poetry…. [W]ith the self losing its solid unity and being able half to detach itself from its bearer, a fundamental shift had taken place in the history of the human mind. Frankel, p. 21

Before Ovid came along, Plato and other ancient philosophers had postulated a self divided by competing faculties of passion and reason. But who had ever represented the subjective experience of these internal divisions with Ovid’s level of modern realism? Even among later poets, who but Shakespeare has represented our divided consciousness so well as Ovid? Indeed, in Ovid’s representations of mental life, schisms of identity and clashes between wishes and realities precipitate solutions where a troubling aspect of self or world is rejected from consciousness. “Time and again,” Fränkel writes of the Amores, “we find Ovid bent on concealing from his own eyes a disagreeable fact; but he also sees to it that the cloak is transparent.” (Fränkel, p. 31) In the Heroides, one of Ovid’s heroines, Phyllis, attests to the same phenomenon: “one is slow to give credence to that which brings pain…. Often I lied to myself….” (quoted in Fränkel, p. 42) True, there are antecedents to Ovid’s notion of denial, too. Consider his telling of the famous story of Jupiter and Io, first in the Heroides and again in the Metamorphoses. Ovid seems deliberately to echo Sophocles. “What is the reason for your flight?” Ovid writes of the nymph Io in the Heroides. (To hide his affair from Juno, Jupiter has turned Io into a cow and Io goes mad trying to run from her new form when she cannot.) “You will never escape from your own face…. You are the same who both pursues and flees. It is you who lead yourself, and you go where you lead.” (quoted in Fränkel p. 79) Whether or not Ovid intended it, the lines certainly call to mind Teiresias’s stunning words to Oedipus in Oedipus Rex: “I say you are the murderer of the king whose murderer you seek.” Ovid, however, accomplishes with his fantastic tales what Sophocles did not attempt: he converts the ancient wisdom written on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi–gnothi sauton in the original Greek (nosce te ipsum in Latin, “know thyself” in English)–into psychological realism that not only depicts inner conflict and denial in personal terms, but actually examines what Freud later called defense mechanisms. That is to say, not all transformation in Metamorphoses is supernatural. In many cases Ovid in fact dispenses with the fantastical metamorphoses and depicts in straight realist terms an emotion being actively revised or altered by another. For example in Book II Phaethon asks his father Apollo whether Clymene (Phaethon’s mother) lied when she said Apollo was his father. His exact words are nec falsa Clymene culpam sub imagine celat (Metamorphoses, II, 37), “if Clymene is not hiding her shame beneath an unreal pretence.” Here Ovid makes the pattern of pain and emotional flight more intricate, more subtle: the particular pain in this case is shame; the particular means of evasion is hiding. At times Ovid upstages Freud to the degree that he uses Freudian terms like “repression” and “transference” in connection with pretty much the same phenomena Freud sought to describe.

erebuit Phaethon iramque pudore repressit, “Phaethon blushed and repressed his anger in shame.” (I, 755) Iovis coniunx … a Tyria collectum paelice transfert in generis socios odium, “the wife of Jove had now transferred her anger from her Tyrian rival to those who shared her blood.” (II, 256-259)

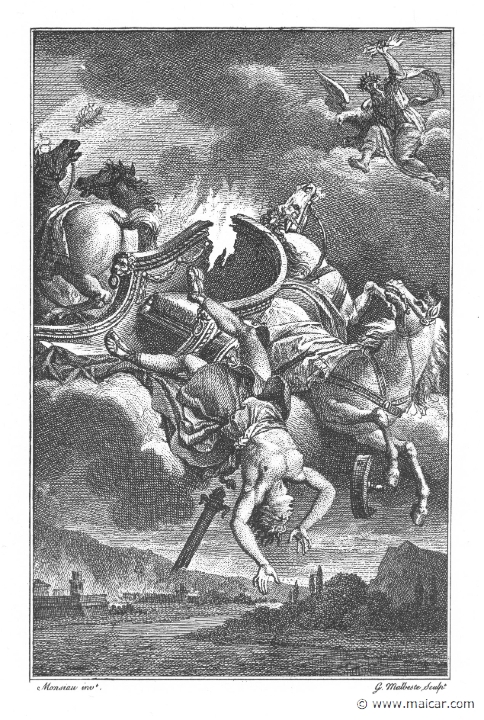

The Phaethon episode in Book II, one of the best in the Metamorphoses, tracks Apollo’s changing emotions in sequence like a psychoanalyst would. After his son Phaethon’s death, Ovid tells us, lucemque odit seque ipse diemque datque animum in luctus et luctibus adicit iram officiumque negat mundo, or “He hates himself and the light of day, gives over his soul to grief, to grief adds rage, and refuses to do service to the world.” (Metamorphoses, II, 383-385) After Jupiter goads Apollo into climbing back into the chariot to light the world, Ovid writes: Phoebus equos stimuloque dolens et verbere saevit (saevit enim) natumque obiectat et inputat illis, “in his grief Phoebus savagely plies the horses with lash and goad (so savagely), reproaching and taxing them with the death of his son.” (II, 399-400) It’s true that the horses were an instrument in Phaethon’s demise, but Apollo knows that they are innocent beasts, that the fault lies most of all with Phaethon himself and with Jupiter, who threw the thunderbolt that killed him–and who, after making a brief apology, had the audacity to threaten Apollo if he didn’t resume his duties. Ovid implies quite unambiguously that Apollo whips the horses in Jupiter’s place, in Phaethon’s place, in his own place. When Jupiter rapes Callisto, one of Diana’s maidens, Ovid writes, huic odio nemus est et conscia silva “She loathed the forest and the woods that knew her secret.” (II, 338) She seems to hate the woods in place of Jupiter (again), because Jupiter is too terrible to attack directly. Perhaps Callisto also hates the woods in place of her own guilt. Ovid continues, quam difficile est crimen non prodere vultu! “How hard it is not to betray guilt in the face!” (II, 447) Freud teaches us that guilt is a major, if not the major, stimulus to repression. Guilt causes people to hide emotions from themselves and from others. More often than not, transformation of ideas and affects does the hiding. Shakespeare knew this before Freud. And Ovid evidently knew it before either one of his great intellectual heirs, as transformative defense mechanisms of displacement and identification abound in his Metamorphoses. I found it most interesting that Ovid describes Nyctimene, a woman who slept with her father and was punished by turning into a bird, as being conscia culpae–literally “conscious of her guilt.” (II, 593) It implies she might also have been unconscious of it. Ovid would have had little trouble understanding Shak and Freud, and it’s obvious that “Ovid’s amazing candor” (Fränkel, p. 58) imparted much psychological wisdom to later ages.