Franz Kafka’s The Trial and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake arrived in English at almost the same time in the late 1930s,* two strange masterpieces without peer except for each other. They differ greatly in style but devote themselves conspicuously to the same agenda: the prosecution of their central characters in the surreal court of conscience and bad dreams.

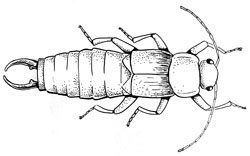

The accused in The Trial is the famous Josef K., arrested for no reason, while The Wake’s accused goes by the juicy, comic handle Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, or HCE as he’s known to Joyceans. He’s a Chapelizod barkeep married to Earth-Mother Anna Livia Plurabelle and a father of three: two boys named Shem and Shaun, and a girl named Issy. Some critics think The Wake represents HCE’s dreams on one long and rainy Dublin night, though Peter Chrisp makes a convincing argument that HCE is a product of The Wake’s dreaming, not the other way around. HCE does not exactly dream The Wake so much as infest it—with his depositions and speeches, his embedded initials, and his farcical, guilt-pronged spirit animal, the earwig. The dream-fog of The Wake is crawling with earwigs—an insect Joyce associated not only with his similarly named protagonist but with one of the Bible’s most notorious O.G.s. It seems Joyce had learned a legend that “Cain got the idea of burial from watching an earwig beside his dead brother Abel.” (Ellmann, p. 570)

HCE’s alleged crimes, however, more closely resemble those of Cain and Abel’s parents, those famed sex offenders known as Adam and Eve (#FirstCrimeFamily). The Wake tries HCE not for murder, but for a sexual indecency committed in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. As in the delirious “Circe” chapter of Ulysses, in which Leopold Bloom is tried for sexual crimes under the garish and hallucinogenic gaslights of Nighttown, witnesses speak and judges render verdicts. The Wake is in some respects a dilation of the Nighttown episode, and HCE’s case is tried and retried again and again throughout the book. Every time you think the case has been adjudicated once and for all, it comes back with the wicked unfairness and relentless absurdity of a Rudy Giuliani press conference at Four Seasons Total Landscaping.

The clearest account of HCE’s alleged crime may be found on p. 107, where his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle defends him from an accusation of voyeurism. The episode seems clearly based on a real episode from Joyce’s adolescence: a young nanny excited his virginal mind by peeing in front of him outdoors. (Ellmann, pp. 418-419) That’s HCE’s crime. Looking and listening with desire. All across The Wake, the curious and horny male gaze violates taboos as it falls not just on unpantsed nannies, but on the bodies of mothers and daughters. No wonder Joyce shrouds The Wake’s contents in darkness!

Voyeurism and sexual curiosity are surely uncomfortable topics; but why does Joyce train such harsh judgment upon them? To modern sensibilities, it perhaps seems odd, like another case of Josef K. arrested “without having done anything wrong,” as Kafka puts it in the first line of The Trial. But conscience doesn’t think like we grown-ups do—not when we’re awake, that is. As a psychological artifact of early childhood, primitive conscience runs amok and out-of-scale in our dreams, judging us like the ancient, crazed God of the Bible, the bearded fruitcake who overreacted so badly to Adam and Eve’s childlike sexual curiosity. The punishment was exile from Eden into the doomed world of Time outside the garden gates. The punishment was, in other words, human mortality. In the Bible, sexual curiosity is literally punishable by death!*

“But abide Zeit’s sumonserving, rise afterfall,” Joyce writes (78.7) in a defiant allusion to that moment in Genesis known to Christians as the Fall of Man. Man sins, God condemns him to death, and Time (Zeit) enforces God’s sentence. Joyce, however, like his creation Stephen Dedalus, “will not serve” God’s sentence.* When Man falls, Joyce does not crawl after him with an hourglass and a chalice full of tears but arrives on his feet with Aquavit and CPR.

Neither Josef K. nor Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker ever receive exoneration. Both Kafka and Joyce instead issue their own verdicts on the childish morality that in the first place dreamed up the kangaroo courts and invested them with authority. At the end of his long career combatting the evils of medieval conscience, Joyce concludes by condemning the oldest and dumbest injustice in the Bible: the verdict God issued to Adam and Eve at the doors of Eden for innocent urges like hunger and curiosity. Dreams may try us for our peccadilloes, blind us, even condemn us to death. Three cheers for our guardians, Kafka and Joyce, who satirize the judges until we laugh ourselves right out of court.

*Notes

The Trial was first published in English in 1937 and Finnegans Wake was first published in book form in 1939. Joyce apparently never read Kafka, but was vaguely aware of The Trial threatening to steal his thunder. (Ellmann, p. 702)

The English words moral and mortal are separated by only one letter, a T. Their Latin roots, mos (behavior) and mors (death) are separated by an R. In Hebrew, the letter R is called resh, and it symbolizes wickedness. Drop a little wickedness into mos (behavior) in the form of an R and it leads directly to mors (death). Mors the poetica of Archie Manglish the Bald: A resh to judgment on the mos-grown sledge sleeve gields remors. O coinpimp! A poem is a mean B.B. My kingdom and a dumb half-denarius for a gelden-hearted whors!

“I will not serve” or non serviam in Latin, is a critically important refrain throughout Joyce’s oeuvre. See Portrait, Penguin ed., pp. 117, 239, 247 and Ulysses, Gabler ed., p. 475.